In the classroom or on the screen — or both, the College of Education continues to rethink where, and how, learning occurs

By Nicole Geary

Have you taken a course online? How about a hybrid program?

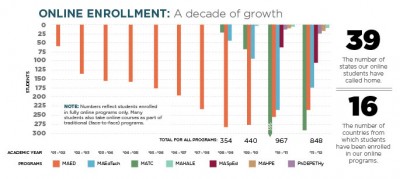

The College of Education led the charge into web-based teaching more than a decade ago and currently claims nearly 900 students pursuing degrees completely online. That population accounts for almost two-thirds of all master’s candidates in the college—and that doesn’t include hundreds of others who now take online courses as part of traditional (face-to-face) programs.

The mission hasn’t changed, but the reach is far greater.

Online programs make higher education opportunities available to more people in more places. Fewer students feel they can sacrifice time and professional commitments to travel to campus, and improving technology and web accessibility means they don’t have to.

More than ever, professors are prepared to foster learning online without sacrificing the quality of instruction that Michigan State University is known for. At least a third of the full-time faculty now teaches online.

BUT BEING ONLINE ISN’T ENOUGH.

Recent media coverage has marveled over making online education even more expansive — take the movement toward massive open online courses, or MOOCs, that can enroll more than 100,000 students in a single class, for example.

In the MSU College of Education, the question is not how many students can be reached. The question is how the online experience — like any other educational experience — can become more meaningful.

“We used to ask questions like whether we should or not, and if the technology will actually work,” said Cary Roseth, assistant professor of educational psychology.

In 2013, he says, instructors must be prepared to ask themselves which software platforms and instructional methods best match the tasks assigned and the students involved. It’s the rationale outlined by the TPACK (Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge) framework, developed at MSU and adopted by educators around the world: rather than being just a vehicle for transmitting knowledge, technology must be an integral component of the teaching and learning process.

Keeping the goals of the course or particular lesson in mind, instructors must think about the boundary conditions, as some refer to it. At what point does the technology being used no longer make sense?

“Up against the boundary, I have to adjust and I start wondering about what I can accomplish,” Roseth said. “Teachers make these kinds of decisions all the time, like what to do in the time left before recess. The online world forces us to think about another context.”

The questions have become:

- WHEN should students work independently (asynchronously) and when should they interact live (synchronously)?

- WHERE should they interact, whether online, face-to-face or some combination of formats (hybrid)?

Graduate education in today’s universities is becoming a complicated mix of these hybrid options, and the College of Education offers one of the most innovative so far: a hybrid doctoral program in Educational Psychology and Educational Technology (EPET).

“The hybrid was developed to meet a need in the mix of doctoral students we wanted to attract to the four-year program — namely, mid-career leaders in education,” said Department of Counseling, Educational Psychology and Special Education Chairperson Richard Prawat. “The resident or face-to-face program was successful in drawing those with recent BA degrees and those who wanted to change careers, but not necessarily those who could not afford to put their careers on hold for a length of time.”

“The hybrid was developed to meet a need in the mix of doctoral students we wanted to attract to the four-year program — namely, mid-career leaders in education,” said Department of Counseling, Educational Psychology and Special Education Chairperson Richard Prawat. “The resident or face-to-face program was successful in drawing those with recent BA degrees and those who wanted to change careers, but not necessarily those who could not afford to put their careers on hold for a length of time.”

With 24 professionals enrolled across 10 states (and one in Dubai), the hybrid program must run completely online — in concert with the traditional doctoral group — except for two weeks each summer. The first students have been able to integrate doctoral coursework and research projects into their world of practice somewhat seamlessly, which in turn contributes more realistic and grounded knowledge to the conversations on campus.

With their faculty leaders, the hybrid Ph.D. students are establishing a brave new model for scholarly community, and a laboratory for the rest of the college.

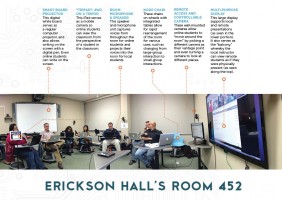

“It’s an urgency that drives innovation,” said John Bell, co-coordinator of the program. For example, Bell has been developing ways for the hybrid Ph.D. students to participate in face-to-face classes via video conferencing systems (GoToMeeting is a favorite) and the use of iPads mounted to desks. The tablets become what he calls “physical avatars,” which represent the remote students’ spaces in the room.

Bell also is director of the new CEPSE/COE Design Studio, a physical and philosophical gathering space for experimenting with and implementing new technologies in teaching. Launched in 2012, professors from every department within the college are testing and employing the use of synchronous technologies, reconfigurable chairs called Node chairs, remote controlled cameras and other equipment in their classes. They are sharing knowledge from their hybrid or online teaching experiences with each other more frequently through roundtable discussions and featured lectures.

The Design Studio builds on existing resources in the college such as the Center for Teaching and Technology and helps professors address emerging needs in their teaching, from creating Khan Academy-style videos with green screen technology to building new online course infrastructure and testing real-time learning assessments that pop up on students’ screens. The studio includes four staff and graduate assistants, two designated classrooms and about $300,000 worth of technology on the fourth floor of Erickson Hall. Research is integrated throughout their projects.

“We are a resource for faculty and instructors, but a very proactive one. We strive to push the conversation forward,” said Bell, whose father Norman retired as a College of Education faculty member specializing in educational technology after more than 30 years.

“The goal is to use our own expertise to guide ourselves.”

Why synchronous?

The first fully online program in the College of Education, the Master of Arts in Education (MAED), started in fall 2001 with just over 50 students. It now claims more than 600 graduates and is one of six fully online master’s programs within the college. Other programs in teaching and curriculum, special education, higher education, educational technology and health professions education all began within the last five years, with more expected in the future.

College of Education faculty members often win awards on campus and from outside organizations (read more about the 2013 Best Practice Award from AACTE) for their use of and research on technology in teaching. One of the top challenges continues to be finding ways to cover the same amount of content from a face-to-face class in a virtual group format. Computer-mediated communication can take up to four times as long, according to MSU Communication Professor Joseph Walther.

Faculty members say synchronous technologies like Google Hangouts for group video discussions and Etherpad for real-time collaborative editing can help cover more material while leading to much richer learning.

And happier students.

When Tanya Wright began teaching in the online Master of Arts in Teaching and Curriculum (MATC)—a program for teachers including those hoping to become reading specialists—students told her that their online courses had often felt too much like independent study. They longed for “real instruction” and discussions that didn’t feel “staged.”

So, like many other professors who find themselves problem-solving in the online world, she got creative. She hosts live Adobe Connect meetings to discuss case studies about struggling readers. The sessions are optional, but more than 90 percent of students participate. Wright also sets up professional book clubs that meet synchronously by time zone. She makes video presentations through which students actually see and hear her, either live or on their own time.

“Even at a distance, students crave interaction with one another and want to know the faculty member as a person,” she said.

When communicating in-person, both teachers and students know more immediately whether their messages are being understood. However, asynchronous interactions are also valuable because they give students opportunities to reflect, review materials or resources and, for those less likely to speak up in large groups, a chance to contribute more actively to discussions.

For instructors, teaching in online or hybrid formats is more labor intensive. They have the added responsibility of sorting through technical problems, time logistics and a stream of student communication that doesn’t start and stop with one class session. But students aren’t the only ones learning through the process.

“I have learned far more about my teaching through online teaching than I have face-to-face,” said Marilyn Amey, chairperson of the Department of Educational Administration, during a college-wide roundtable event last fall. “It’s caused me to really question my assumptions about learning, about how I know students are learning. It’s changed, fundamentally, how I teach a face-to-face class as a result.”

The hybrid experiments

Synchronous learning takes on different dimensions with hybrid courses, in which students gather live at least some of the time. In vertical hybrids, students flip between attending face-to-face classes and engaging in various web-based interactions. In horizontal hybrids, some students see their instructor in person while others participate from elsewhere.

MSU teaching interns placed in Chicago schools, for example, rely on Polycom video conferencing to connect with fellow interns and their instructors on campus. Teachers and school leaders enrolled in the off-campus K-12 Educational Administration master’s programs based in Birmingham and Detroit learn through a mix of face-to-face sessions and online activity — both asynchronous and synchronous — designed to mesh with their professional lives.

Professors such as Kenneth Frank from the Measurement and Quantitative Methods faculty alternate teaching between two locations. Others including Roseth, Matthew Koehler, Punya Mishra, Christine Greenhow and Douglas Hartman are experimenting with connecting students from multiple locations to a single live classroom.

In Erickson Hall’s Room 452, they are testing ways to make remote students feel almost as though they are sitting amid the group, able to see and hear all details of class.

And participate in small groups, too.

One night during Mishra’s CEP 917 course in Room 452, Tracy Russo sat at her laptop, silently chatting and creating a document along with one student sitting on the other side of the room and two others sitting in their homes hundreds or thousands of miles away. In total, 10 students were in the room and 10 were off-site. When the whole group came back together, the faces of students from Texas, Idaho and Utah appeared on the large screen, which they call “the balcony.”

The groups struggled a little to summarize what they had just communicated with each other (through writing) on Etherpad: “You can spew a bit more online, but it’s hard to rein it in at the same time,” said Andy Driska, a kinesiology doctoral student in the class.

Sometimes, an iPad attached to a tripod serves as a camera that can be moved around the room to help remote students follow the person who is speaking more closely (and read facial expressions). They jokingly call it the TriPad and, yes, it is not a perfect system.

Yet.

Students and faculty in the College of Education embrace a spirit of experimentation and a shared goal no matter what new technology is being integrated: to improve learning.

According to Professor Patrick Dickson, the Design Studio and EPET hybrid program are beginning to add powerful contributions to a conversation about best practices in teaching with technology that is long-running within the college—and rare.

“There are not many institutions that have this kind of discourse,” he said. And graduates of the college, who have taken online or hybrid courses and/or taught them themselves, are leaving with the knowledge they will need to lead future models in K-12 and higher education settings.

With online learning integrated into every discipline offered, “it’s in the DNA of their study,” Dickson said.

“Our students will, no doubt, be instructors online. They will be collaborating and writing with people at a distance.”

It is the reality, ready or not.

Center for Teaching and Technology

Housed just off the lobby in Erickson Hall, the Center for Teaching and Technology provides a variety of services to help faculty, staff and students use technology in teaching and learning. This includes offering workshops, lending equipment such as cameras, digital audio recorders and iClickers, and providing in-classroom support. In 2012, the center launched an iPad loaner program allowing instructors and their students to explore the device’s potential throughout an entire course.