Reflections on Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” Speech and Civil Rights in Education

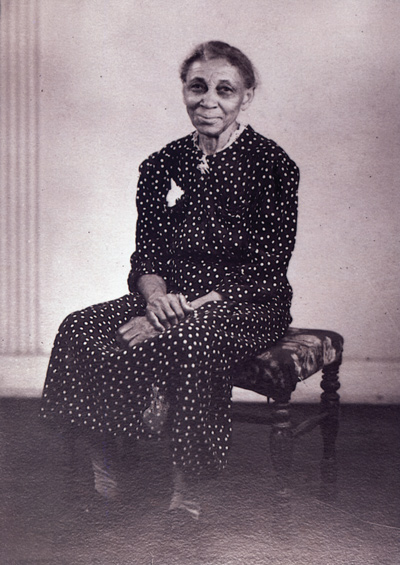

My maternal great-grandmother Dorenda often said she was born in the year peace was declared. She meant the year slavery was abolished in the United States. Born free in 1863 to a slave mother also named Dorenda, she farmed land and raised 15 children in Arkansas during a time when the ability to read and write represented humanization, liberation and personal agency for millions of freed slaves. I believe that both Dorendas—one born into slavery and one born free—imagined a future in which their descendants could live their “American Dream” in a country where human bondage would be declared illegal, and the benefits of a quality education would be available to all. I imagine these two Dorendas who came before me dreamed big dreams while working in cotton and corn fields, and rocking babies to sleep in small, run-down plantation shacks.

Despite my ancestors’ hopes, 100 years later Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. professed to the world that “the Negro is still not free” in his 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech. A century after my great-grandmother was born into declared freedom, Dr. King reminded our nation of the crippling effects of segregation and “chains of discrimination” still plaguing black people in the United States. And now 51 years after his momentous speech, 60 years after Brown v. Board of Education (1954), and 50 years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act we must ask: how far have we come in achieving racial equity in the United States? Many black and brown people in this country still live on “a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of prosperity.”[i]

Sadly, the current state of our K-12 educational system is a perfect example of how America continues to default on the promissory note Dr. King spoke of in 1963, specifically as it relates to the education of students of color. While we have made progress in many sectors, we have regressed in our efforts toward racial equity in education. With education being the marketplace it is today, there has been a flight toward charter schools and private education and a retreat from public education as it was originally envisioned. These practices have resulted in the resegregation of schools in areas that are already underfunded and under-resourced, and lower quality education for those students.

Carter Andrews’s maternal great-grandmother Dorenda (taken in the 1940s).

But we cannot let the dominant narrative of educational despair for many black and brown youth thwart our acknowledgment of the gains made by oppressed peoples through hard work, perseverance and resilience. In many ways I am the product of my foremothers’ dreams: I grew up in a suburban, middle class, racially integrated neighborhood in Decatur, Ga. In the 1980s, my parents enrolled me in the Majority to Minority (M to M) [ii] busing program in my county, believing that my sister and I would receive a better education in the schools on the north side of the county.

In an effort to further integrate, the M to M program allowed any student of the majority race in his or her home school to attend another school in the county in which he or she would be the minority. I attended predominantly white schools from grades 8 through 12 in Stone Mountain, Ga. Attending these schools had many benefits: access to “highly qualified” teachers, current textbooks and technology, field trips that introduced me to the social and cultural capital of mainstream America, extracurricular activities, and Advanced Placement and honors courses.

However, my experiences in school entailed emotional and psychological challenges, resulting from what scholars of color call racial battle fatigue.[iii] In these new school environments, I learned how to maintain academic success and a strong racial identity. While I had several white teachers and a few black teachers who were instrumental in my success, achieving academic success in a racially hostile environment came at a price. Feelings of situational self-doubt and intellectual inferiority in the classroom resulted from being the victim of racial micro-aggressions committed against me most often by my white peers and teachers. This racism was sometimes overt and at other times subtle in its manifestation. I was acutely aware of my minority status. My experiences are echoed in research about and memoirs of African American students attending racially integrated schools and majority-minority schools where the teaching staff was—and still is—predominantly white post-Brown.

As a high-performing black student, I was often referred to by teachers as “the only one” or “one of few” in this category, which characterized me as succeeding despite their expectations. In the classroom, I was not always allowed to be an individual, but was often defined by my racial group membership. More often than not, I felt compelled to speak and behave in ways that would situate me as the representative of my racial group. In his speech, Dr. King speaks of “veterans of creative suffering”—those who endured racism in its various forms and overcame its harsh sting. This creative suffering represents a type of resilience to the discrimination experienced by students of color despite federal laws to protect them. I often wondered about the lack of students of color in my Advanced Placement courses and academic extracurricular activities. It was easy for teachers to identify my intellectual capabilities based on a record of high performance; but I saw too many black students labeled as incapable based on adults’ limited interactions with them in an academic or social setting.

When I became a high school math teacher, I was very passionate about recognizing and growing the intellectual potential of underperforming students of color. Having taught in urban, suburban and private school settings, I realized that for many of my underserved students I was their only advocate within the educational system. My years spent as a black student and K-12 educator provided me with great insight into the crippling effects of integration, segregation and discrimination for black and brown youth in the United States.

A dream deferred: We are not ‘post racial’

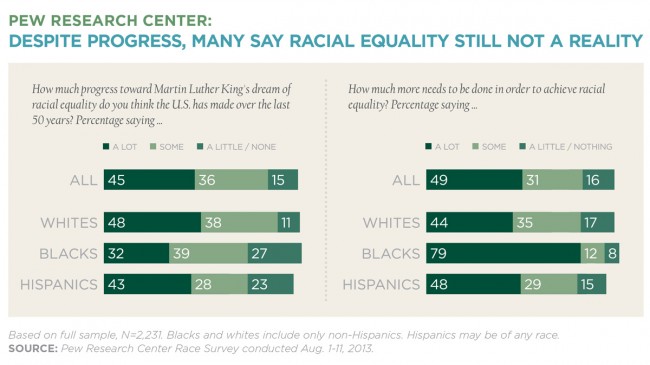

Despite the plethora of research that continues to identify racism as one of the factors contributing to academic underperformance of students of color in our schools, many believe racism is a thing of the past. However, a 2013 survey by the Pew Research Center found that less than half of all Americans believe the country has made substantial progress toward racial equality, and many believe there remains a lot of work to be done toward this goal (see graphic below).[iv]

In fact, the survey found that African Americans are more likely than whites to say that blacks experience less fair treatment by police, the courts, public schools and other community institutions. The dance of racial progress resembles a two-step forward, one-step backward pattern. While data from the Pew Research Center indicates high school completion rates between blacks and whites have narrowed, white adults age 25 and older are significantly more likely than blacks to have completed at least a bachelor’s degree.

In my recent co-edited volume with Frank Tuitt, [v] we argue that our nation’s schools are not created equal and do not receive equal protection from the policies, practices and directives that differentially affect or disadvantage students based on race. We liken this practice to environmental racism, arguing that the nation’s schools remain contaminated with pollutants that prevent numerous youth of color from fulfilling the promise of racial equity.

There are many current examples of racism that highlight our distance from becoming post racial any time in the foreseeable future. For example, the overt racial assaults on Barack Obama’s character throughout his two terms as the first black president of the United States are one indicator that we are not a colorblind society. Additionally, the senseless killing of young black men and women (e.g., Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Fla.; Oscar Grant in Oakland, Calif.; Jordan Davis in Jacksonville, Fla.; Renisha McBride in Detroit, Mich.) for simply having black skin are modern-day reminders of cases like Emmett Till, an adolescent African American male murdered in Mississippi in 1955.

If we look beyond the black community for examples, anti-bilingual initiatives in several states (e.g., California, Massachusetts, Colorado) and the ban on ethnic studies in Arizona remind us that the right to learn in one’s native tongue and about non-white cultural groups in school is not considered a civil right. Furthermore, structural racism continues to manifest itself as a toxin in schools through the disproportionate presence of students of color, disabled students and language-minority students in special education and lower-level general education courses, as well as the number of suspensions, expulsions and arrests for disciplinary actions that should have been handled by classroom teachers or principals. Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was designed to protect students from these types of practices.[vi] These same subgroups of students suffer the effects of bullying at disproportionate rates to their dominant group counterparts.[vii]

Across social institutions in society, the evidence is overwhelming that racial inequity is pervasive, and schools are a microcosm of the larger society. The disillusionment primarily by mainstream America that we are post racial underscores an inability or refusal to acknowledge the poor outcomes of African Americans—and other people of color—in education and other areas (e.g., home ownership, health and employment) and reminds us that post racialism in the United States is a myth.

Realizing the dream

We cannot afford to remain pessimistic about the future. Despite the overwhelming ills of education in the United States since King’s speech and the passage of Brown and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, I still believe Dr. King’s dream can be realized. In 1954 Chief Justice Earl Warren said, “In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right that must be made available on equal terms” (Brown v. Board of Education). Sixty years ago education was defined as a civil right, and today we purport the same message in our political rhetoric. Yet the quality of education differs across neighborhoods, towns, cities and states. Every American citizen must become compelled to advocate for an educational system that affords every child the opportunity to achieve his/her success and equips them to do so.

I remain hopeful that my three daughters and other children of color can experience public schools as nurturing of their multiple selves (racial, academic, etc.); that schools will be places where they are able to develop positive same-race and cross-race relationships with teachers, other adults and their peers; and that they can say they never felt intellectually inferior to anyone simply on the basis of skin color. Racism and other forms of oppression must be eradicated. The enactment and widespread presence of educational inequity doesn’t allow for any of us to experience our full humanity. Furthermore, what is inequitable for one negatively affects all; the individual good is intimately tied to the collective good. Because schools are touted as being the great equalizer, they have to become institutions where equality and equity are normalized. Students who have been traditionally marginalized on the basis of race, ethnicity, language, social class, sexuality and gender must experience schools as places where their identities are affirmed and achievement is possible for anyone, regardless of racial background.

It is not my intention to offer solutions in this reflection. However, I’m suggesting a tall order that will require a lot of critical self-reflection on the part of educators, policymakers and the common citizen. Now is our time to rise to “the sunlit path of racial justice” (MLK speech, 1963). We have been in a moment of urgency for 51 years, and now perhaps more than ever we are admonished to consider how racism and other forms of oppression are starving the economic and social prosperity of communities of color and endangering the livelihood of our democracy as we understand and know it. Realizing the dream of racial equity in education requires rewriting the deficit narrative about the intellectual capacities of students of color and utilizing asset-based practices in the classroom. We have evidence of learning environments where black and brown youth thrive academically without subtraction of their cultural identities. We must look to these learning spaces for insight into wide-scale change across the system. Langston Hughes once posed the question, “What happens to a dream deferred … does it explode?”[viii] We cannot afford for Dr. King’s dream to explode. Our very survival as a democracy rests on the ability of individuals and groups to realize their full potential through equal access to opportunities for happiness and social mobility.

Dr. King believed that 1963 was not the end but the beginning of transformative change. As we remember his legacy and those of civil rights struggles gone before, I hope that in 2014 we as Americans envision the start of a journey for every citizen in this country to critically reflect on how they can work to enhance the quality of life for those who are oppressed. It is a project of humanization that has at its core the end to racism in this country. While this may not happen in my lifetime, I am devoted to working wholeheartedly toward this goal. Ultimately we are all in a struggle for embodiment of our full humanity, and our commitments to personal and collective pursuits can result in transformative change.

About the author

Dorinda J. Carter Andrews conducts research on race and equity in education, with a particular emphasis on black student achievement in urban and suburban schools. A faculty member in teacher education, she is instrumental in the College of Education’s urban education initiatives.

References:

[i] Martin Luther King Jr., “I Have a Dream” (speech, Washington, D.C., August 28, 1963).

[ii] DeKalb County School District, The History of Education in DeKalb County: oldwww.dekalb.k12.ga.us/about/history.html

[iii] Smith, W. A., Yosso, T. J., & Solórzano, D. G. (2006). Challenging racial battle fatigue on historically white campuses: A critical race examination of race-related stress. In C. A. Stanley (Ed.), Faculty of Color: Teaching in predominantly white colleges and universities. Bolton, MA: Anker Publishing.

[iv] Pew Research Center, “King’s Dream Remains an Elusive Goal; Many Americans See Racial Disparities,” Aug. 22, 2013: www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/08/22/kings-dream-remains-an-elusive-goal-many-americans-see-racial-disparities

[v] Carter Andrews, D. J., & Tuitt, F. (2013). Contesting the myth of a ‘post racial’ era: The continued significance of race in U.S. education. New York: Peter Lang.

[vi] U.S. Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights: www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/hq43e4.html

[vii] PACER Center, National Bullying Prevention Center: www.pacer.org/bullying/about/media-kit/stats.asp

[viii] “Harlem,” by Langston Hughes: www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/175884