From floating to flying: Mentor helps MSU faculty member launch unlikely academic career

By Nicole Geary

Terry Flennaugh found out how powerful a mentor can be the moment he got the call. He could not believe it, but a college admissions officer was saying yes.

“I had been told ‘no’ in a lot of different contexts my whole life,” he said. “I was not one of the kids supposed to be at UCLA.”

By Flennaugh’s junior year at James Logan High School in the San Francisco East Bay area, he was barely a B student, having never been recognized as gifted by his teachers. To make matters more difficult, his mother, who did not graduate from high school, wasn’t having conversations with him about pursuing advanced classes or higher education.

“Most of the time, I was sort of floating through,” he said.

The only place he shined was on the speech and debate team, which he reluctantly joined freshman year at the urging of coach Tommie Lindsey Jr.

Mr. Lindsey isn’t the kind of guy who takes no for an answer. As Flennaugh describes it, once Mr. Lindsey saw Flennaugh’s college potential, he “forced” the young oratory champion to negotiate contracts with teachers that would allow him to make up classwork and improve his grades.

When his first application to UCLA was denied, Mr. Lindsey urged Flennaugh to appeal. He helped him obtain letters of recommendation, and arranged a meeting with an admissions staff person. Mr. Lindsey even drove across town to personally tell the university’s vice chancellor, who was visiting the area for a special event, about Flennaugh.

Tommie Lindsey teaching in his classroom. Photo by Craig Lee, San Francisco Chronicle.

After three appeals, Flennaugh became one of just five students in his class headed to University of California’s Los Angeles campus and quite possibly the last person admitted that year (provisionally). He started his academic career in overflow housing with five roommates, facing a mountain of fears and financial challenges.

Ten years later, he left UCLA with a doctorate and was hired to join the faculty of one of the nation’s top-ranked teacher education programs. Flennaugh is now an assistant professor in the Michigan State University College of Education and a leader of the college’s urban education initiatives.

“I always knew Terry had a passion for education and for helping the underdog. He was in that situation and never gave up motivation,” said Mr. Lindsey, who is still teaching and coaching. “But someone of his intellectual prowess should never have been in a situation where he was slighted in such a way.

“It shows the ineffectiveness of our education system.”

How does his background influence his work?

Flennaugh knows what it’s like to feel disconnected, unnoticed and even discriminated against in school. He also knows how much teachers can transform—or demolish—students’ dreams.

He is not shy about describing his own experiences to teacher candidates at MSU, especially in TE 250, a course that requires students to reflect on issues of equity and opportunity in schools.

“Simply believing or not believing in your students can make the biggest difference in their lives,” he tells future teachers. “Unfortunately, teachers were often the ones who made me feel I couldn’t accomplish anything.”

Except for Mr. Lindsey, who has become something of a celebrity for the unorthodox, tenacious ways he propels black male youth in northern California. The success of his forensics team, of which Flennaugh was a leader, became the subject of a documentary film, “Accidental Hero: Room 408.” Oprah Winfrey presented the Logan High forensics team with her $100,000 Use Your Life Award in 2003 and, in 2004, Lindsey received the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship.

“It’s not a coincidence that Mr. Lindsey was the only black male teacher I ever had,” Flennaugh says. “The truth is, had I not had the respect that I did for my coach at that time, being on the speech team and seeing what he did for others, then I would not have gone through what I did.”

What happened when he got to college?

At UCLA, Flennaugh was thrilled to be paving his own career path. But he also had a fear of failing that never went away, even during his last semester as a PhD student.

“I think that speaks to what a lot of students of color experience at predominantly white institutions,” he said. “The reality is, I did well at UCLA. The longer I was there the more I realized that I could be there, and that peers of mine could have been there had they just gotten the opportunity.”

He enjoyed the freedom to become engaged in issues that mattered to him at UCLA, and he became “unapologetically committed” to fighting against forms of discrimination affecting his peers, as an activist, researcher and mentor to younger students.

“My goal was to transform the institution so it would be more inclusive and responsive to the community in ways it not always had,” he said.

Flennaugh’s doctoral advisor was Tyrone Howard, a leading scholar on equity and access for black males in education. In fact, in 2009, Flennaugh helped Howard establish the Black Male Institute in UCLA’s Graduate School of Education and Information Studies.

So, why did he come to Michigan State University?

“What stood out was the fact that the College of Education was so explicit about its commitment to urban populations,” Flennaugh says.

Even though the California man had to move across the country, he has found an academic home where he can live his passion for improving education for students of color.

He supports doctoral students who share an interest in academic identity formation, and he works closely with big-dreaming teenagers from Detroit and Chicago who spend time at MSU through the Summer High School Scholars college preparation program.

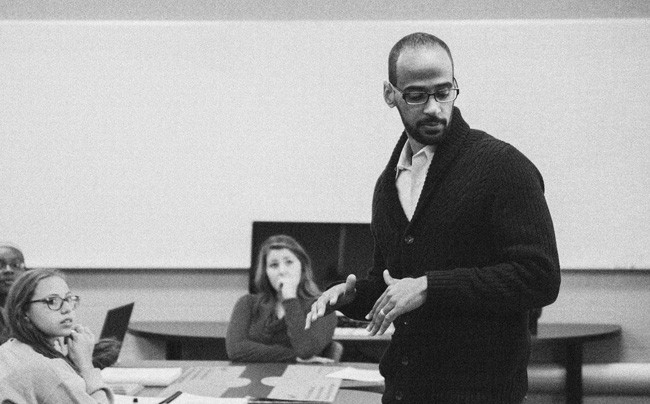

Terry Flennaugh interacts with teacher education students in TE 250, a course that explores issues of social justice.

His research ranges from studying the impact of the specialized Urban Educators Cohort Program for future teachers, to evaluating a school academy for homeless youth in Detroit and exploring what makes single-sex learning spaces effective for black males. Classes and programs exclusively for black males are growing as a way to meet the particular needs of the population, he says, but not all are effective.

California is one place where this trend is emerging. Not surprisingly, Mr. Lindsey is a pioneer. In a freshman life skills course he teaches specifically for African American males, Mr. Lindsey has been able to improve achievement for students by almost three grade levels. Although high school graduation rates remain alarmingly low for black males in much of the state, at least 85 percent of the students in Mr. Lindsey’s forensics program go on to four-year colleges. About 200 kids participate.

As an educational researcher, Flennaugh has often returned to Logan High School to study the factors that make those giant leaps—and subsequent opportunities—possible. While there, he reconnects with his mentor and gives him pointers on assessment and data collection.

When Mr. Lindsey retires next year after 40 years in education, he says he will remember what he and his students endured: all-white forensics teams assuming they could not compete, judges dozing off while they were performing, even restaurants refusing to serve them in suburban neighborhoods.

He will also take pride in knowing what some of his star pupils have achieved in life—and the lives they have yet to change.

“All the hard work that goes into it, it all pays off when you see someone like Terry make it through the cracks,” said Mr. Lindsey, who believes the education field will be “stymied” by Flennaugh’s contributions as a scholar.

“Michigan State is fortunate to have the kind of mentor he is going to be to future teachers … You can’t learn to be a teacher through a textbook—it has to come from the heart.”

On the Web