How focusing on students’ community and cultural strengths can change the classroom

How focusing on students’ community and cultural strengths can change the classroom

By Lauren Ebelt

Looking through the window of a classroom, it seems easy to define.

It is a learning space, whether with easel and paint, computer and keyboard or paper and pen. A teacher leads the way with lessons. Often, support comes from the outside community of friends, family and collaborators.

In any classroom across the United States, the situation is mostly the same.

But, at the same time, it isn’t.

Every learning space has unique layouts, books, artwork, homework prompts. The teachers are enthusiastic about different chapters, units, theories, methodologies.

And the students who fill the spaces come with many differing experiences and languages, and with unlimited skillsets, talents and backgrounds.

No two spaces are the same. No two teachers are exactly the same. No student has the same characteristics as another.

So why teach all students the same?

Rampant standardized testing and heightened accountability can make it difficult for teachers to move beyond mandated curricula and transform their approach. That is why scholars at the Michigan State University College of Education are revealing the keys that unlock the most potential in every classroom. They are taking steps in and out of schools to find better ways to connect and engage with students and families, collecting themes and practices from the many cultures they represent and incorporating them into the curriculum.

Their research is creating evidence and momentum for a new type of classroom: one that is a student-focused, student-driven and student-empowered learning space bursting with creativity, engagement and excitement.

Edwards

Home is where the data is

“If you were to go to the doctor and say, ‘I have chest pains,’ he wouldn’t just immediately say, ‘Here is your treatment.’ He would look at your family history, when you ate last, what you were doing when the pains started and many more things before deciding how best to treat you,” Professor Patricia Edwards says.

“Why don’t we do the same for our students? Why don’t we look at their home environment, their interests, their strengths when determining the best teaching methods for that child?”

Edwards, a nationally renowned expert in literacy, has long been an advocate for exploring the strengths of a student’s background, family and culture and how they can relate to their success in school. In her latest book—“New Ways to Engage Parents: Strategies and Tools for Teachers and Leaders, K-12,” published in May 2016 through Teachers College Press—Edwards says the family of the child can be a cornerstone for learning.

Edwards explains how the power of data, demographics and parent-teacher engagement can be harnessed together to create a better learning environment for all students.

“Teaching focuses a lot on subject matter, but we need to study who our subjects are,” Edwards argues—and that ties into one of the first steps in her book. “If you go into a school with what you think is going to happen, it’s not going to work. You need to create demographic profiles of your students and their community, then analyze it.”

“Teaching focuses a lot on subject matter, but we need to study who our subjects are,” Edwards argues—and that ties into one of the first steps in her book. “If you go into a school with what you think is going to happen, it’s not going to work. You need to create demographic profiles of your students and their community, then analyze it.”

How involved are the parents in their student’s learning? What does the parent know about the child that might help the teacher in the classroom? These questions can help in the way a teacher approaches a student, and in the book, Edwards gives some ideas on how to best reach out to, and continue to connect with, parents.

She believes that many schools rely too heavily on traditional, one-way communications, like handbooks, report cards and newsletters that the student brings home—and that the parent may never even see or read. Instead, Edwards encourages educators and parents to tap into the modern benefits of technology and use two-way communication tools, such as email, texting and Skype or Google Hangouts. In this way, parents and teachers can converse not only about what is going on with the student, both in school and at home, but what can help inform decisions on how to move forward with the student.

In the end, Edwards believes understanding more about the student’s home environment and connecting with their family can make all the difference and is a vital solution in creating an individualized learning environment.

“You would try every possible medicine to help get a child well, why would you not try every method to get the child to learn?”

Paris

Joining and Sustaining

For Django Paris, understanding the background of a student is just the first step. His research involves studying languages, literacies and literatures among youth of color. His focus is on sustaining these practices, and how they can be joined in classroom learning.

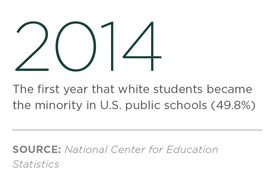

Previous research had highlighted the importance of making teaching and learning relevant to all students. In 2012, Paris took that thinking a step forward and coined the term “culturally sustaining pedagogy.” The term supports the changing face of the American student, and aims to recenter the way students are taught.

Indeed, the “typical” American classroom looks very different than in decades before. In 1970, approximately 80 percent of public school students were white. Today, more than 50 percent of public school students are students of color. They come from increasingly diverse families, and speak more languages than ever before.

“U.S. public schooling tends to be centered in monocultural and monolingual norms of being, but also in achievement and the way achievement is measured,” Paris said in a recent interview with Education Week blogger Larry Ferlazzo. “Those norms are really centered around practices that are common in white, middle class, monolingual communities and not really centered in a multilingual reality for so many young people now and going forward.”

“U.S. public schooling tends to be centered in monocultural and monolingual norms of being, but also in achievement and the way achievement is measured,” Paris said in a recent interview with Education Week blogger Larry Ferlazzo. “Those norms are really centered around practices that are common in white, middle class, monolingual communities and not really centered in a multilingual reality for so many young people now and going forward.”

Paris, associate professor of language and literacy, has a line of research that goes against those norms in schools: The practices, languages, literacies and the culture of all students are important and shouldn’t be overlooked.

“For too long, [teachers have] been inviting some literature, some language or community practice into the classroom, only to get to the better practices, language, literacy, literature or the more accurate history. What we’re talking about is something very different,” he said. “We’re talking about courses where students are centered across academic activities. That doesn’t mean it is uncritical and they don’t extend what they know and can do. That does mean that the outcome is that they have those practices intact and hopefully they know them in ever more critical ways.”

Paris recently collaborated with April Baker-Bell, assistant professor in the Department of Writing, Rhetoric and American Cultures at MSU, and Davena Jackson, a doctoral candidate in the Curriculum, Instruction and Teacher Education (CITE) program. They researched critically joining the African American language (AAL) in Jackson’s urban high school classroom. The language is a systematic variety of English and is informed by the past and present of the African American culture.

Another related research project examined a teacher in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula who developed a curriculum using the language and culture of the Anishinaabe tribe as a subject with his predominantly Anishinaabe K-8 students. Several indigenous tribes use the language across the Great Lakes region.

Both studies, presented at the National Academy of Education in Washington, D.C. in 2015, examined how the teachers concentrated on the values of the respective language in their schooling, and how the students identified as speakers.

Throughout these studies, and in much of Paris’s research, he is interested in how educators can connect with and honor in critical ways the literacies students are already engaged in. His critical work on race and equity has been celebrated in several ways, most recently with the 2015 AERA Division G Early Career Award, which honored him for advancing the study of education and social contexts.

Throughout these studies, and in much of Paris’s research, he is interested in how educators can connect with and honor in critical ways the literacies students are already engaged in. His critical work on race and equity has been celebrated in several ways, most recently with the 2015 AERA Division G Early Career Award, which honored him for advancing the study of education and social contexts.

“Young people are reading and writing more than they ever have,” Paris said, when explaining the different literacies that are woven into youth’s lives. “They’re reading, writing, using digital, visual and multimodal ways of communicating. They’re expressing themselves with graffiti, hashtags, memes and essays. As educators, we need to think deeply about what practices they’re engaged in, and why. For what purpose?”

Like Edwards, Paris believes that understanding (and embracing) the literacies gives teachers a way to focus on the strengths of the students. By asking what, how and for what purpose youth are utilizing these methods of communication, educators can link them to a more inclusive environment for all.

“[Educators can] think about who the students are in their classrooms, and what language varieties and languages they use in their communities and in their schools. Start thinking about ways to bring those meaningfully into the classroom,” Paris said. “And rather than to simply think about bringing it into the classroom, think about joining it. What are young people doing in digital spaces? On mobile devices? And why not bring those into the classroom? The start is an invitation.”

Watson

Striking the right chord

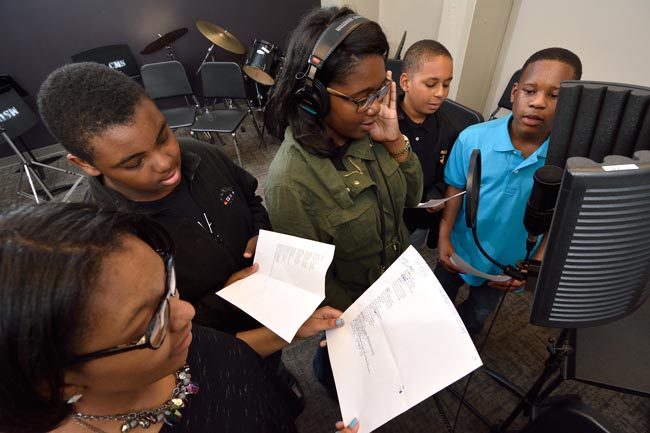

In Detroit, Mich., 35 teenagers wrote, performed and engaged with music through the Verses Project: Exploring Literacy through Lyrics and Song. From February through May 2016, the students gathered at the MSU Community Music School-Detroit to learn from artists, poets and songwriters as they considered their passions and how they connect to their studies.

“We are exploring topics that students want to say, things that they’re interested in,” said Assistant Professor of English education Vaughn W. M. Watson. New to the College of Education faculty in 2015-16, he is part of the MSU team bringing the Verses Project to life in its first year. Watson is studying the impact of the program with co-principal investigator Juliet Hess, assistant professor in the College of Music. Others involved include Mark Sullivan, associate professor in the College of Music; Matthew DeRoo, a doctoral candidate in the CITE program; and Kayla Makela, an undergraduate student.

Students practice songs and listen to lessons as part of the Verses Project. Photo by Harley J. Seeley Photography.

Watson and Hess developed the curriculum for the 15-week program, which included teaching songwriting, composing, music-making, performing, mixing and recording. The project is a collaboration of the Marshall Mathers Foundation, Carhartt, the Community Music School-Detroit and scholars at MSU to bring student pastimes, community and learning together into a powerful partnership.

Watson’s past and present makes him the perfect fit to be a part of the Verses Project. A former teacher in Brooklyn, N.Y., Watson’s research focuses on the interplay of literacy learning, and how the identities of youth of color are reimagined across things like hip-hop and education.

Growing up outside of Philadelphia, Watson listened to all sorts of music, and experienced what he calls a Philly soul curriculum.

“[The music] affirmed my space in the community,” Watson recalled. “It helped make sense of the broad notions of literacies and music. And it helped me become interested in what happens when classrooms allow you to bring forth literacies, musics and identities.”

To Watson and Hess, a former full-time public school music teacher, literacies and music are an integral part of who a person is. Everyone participates in music, they say, and in many ways: Dancing, listening, even promoting a concert are all connections to the music that surrounds us.

Photo by Harley J. Seeley Photography.

Hess believes music is just as important in the classroom as well. “It is a medium for students to find their way in,” she said. “It’s a place to find your self, your voice.”

The goal of the project is not only to get students more interested in music, reading and writing, but also to explore more of themselves.

“We’re seeing how youth are asserting themselves as contributors of and participants in their communities and in their schools,” Watson said. “[The students’] music and beats are drawn from their own lived experiences and communities, and now they’re expressing it in song.”

While the first iteration of the program has ended, Watson, Hess and others are looking forward to the future. The program will continue during the summer of 2016 through two week-long camps, and start again in the fall with 60 students. Watson and Hess also plan to make the project curriculum available to K-12 public schools.

“There are so many literacies and musics that these students are enacting. How can you build curriculum around these literacies? Teachers can take a strength-based stance as opposed to saying, ‘Here’s what the students can’t do,’” Watson added. “Our approach to teachers’ practice in the classroom is to build upon what the students are already doing.”

Speaking up

Poet, MC and teaching artist Myrlin Hepworth, a speaker in the Urban Education Speaker Series, talks to an engaged crowd at MSU in October 2015.

While research is being done to change today’s classrooms, the college remains dedicated to teaching tomorrow’s educators.

The Urban Education Speaker Series started as a campaign in 2011-12 to feature the work of emerging and leading scholars whose work speaks to helping students in marginalized communities.

The series has grown and developed over the years, and since spring 2015, has been in the hands of Terry Flennaugh, assistant professor and coordinator of urban initiatives in the College of Education. Flennaugh was selected for the position by Sonya Gunnings-Motion, assistant dean for student support services and recruitment, who had previously worked with him through the Summer High School Scholars Program and the Urban Educators Cohort Program. Both of those programs cultivate future teachers dedicated to serving in urban communities.

Flennaugh has been instrumental in bringing several scholars to campus for the speaker series who, among other topics, focus on equity in schools, critical literacies and emancipatory education in their careers.

A group of faculty in the college whose work revolves around urban education helps Flennaugh decide who would best fit the missions of the speaker series. Often, they are scholars whose work MSU students are already reading in their classes. A poet and critical race scholars were among those who spoke during the 2015-16 academic year.

“The speakers wouldn’t be here if they didn’t do work concerned with empowering all students, especially students most negatively impacted by systems of marginalization,” Flennaugh said. “Their work is in line with MSU’s mission to prepare our own teachers to be effective for all students.”

Flennaugh, whose research focuses on the educational experience of students of color in urban contexts, was also integral in facilitating “Making Relationships Work: A Summit on Black Male Academic Success and Inclusion.”

On the web

The Verses Project:

See more about the Verses Project through this clip, featured on CBS Detroit: cbsloc.al/27HJoQu

Hear more from Watson and others involved in the project in this video produced by the Community Music School-Detroit: http://bit.ly/29fPSSa

Paris Q&A:

Django Paris was featured in Education Week through a two-part series in May 2016. Read his thoughts on meeting the needs of students of color (bit.ly/edweekQA1) and culturally sustaining pedagogy (bit.ly/edweekQA2) to learn more about his research.