School districts could be misidentified, avoid assistance or even lose funding under Michigan’s new law

By Rachel White

By Rachel White

Doctoral Candidate, Educational Policy

whitera3@msu.edu

Michigan school districts1 are facing unprecedented levels of fiscal distress. Enrollment continues to decline, retirement system obligations continue to increase and the minimum allocation each district is guaranteed from the state School Aid Fund has not kept pace with inflation. Moreover, as a greater proportion of families are exercising their right under Michigan’s open enrollment system to send their child to a school outside their home district, school districts have found it difficult to predict future enrollment. Given that Michigan school districts are primarily funded via a per-pupil allocation from the state, some districts have found it incredibly difficult to make budget predictions.

As a way to notify school districts of potential fiscal distress before they are in the red, Michigan enacted a new early warning policy for school districts in 2015. The state Department of Treasury began implementing this new system in August. If the law is implemented as written, it may accurately predict financial stress in some school districts. However, the incredibly complex, yet rudimentary system will likely lead to misidentification of many districts: some that need help with financial planning and budgeting may not get it soon enough and others that have successfully managed their finances may be required to expend unnecessary resources.

Measuring school district fiscal distress

The financial condition of a school district may be defined as its ability to balance recurring expenditure needs with recurring revenue sources, while providing required educational services on a continuous basis. Financial conditions are affected by a combination of environmental, fiscal and organizational factors that change over time; thus, no one static measure can fully capture the financial condition of a district. Determining which measures to use is akin to measuring human health in the medical field: Would you prefer a doctor who only measures whether a patient has any single symptom at the time she is in the office—e.g., does she have an irregular heartbeat or shortness of breath today? Or, would you prefer a doctor who measures a patient’s current health and discusses what that could mean for the future—e.g., how her blood pressure and resting heart rate changed over time? What do these trends imply about the risk of a heart attack? Unfortunately, the State of Michigan’s system to assess financial conditions of school districts is like the shortsighted first doctor.

Michigan’s early warning system for school districts is not entirely new; since 2012, schools have been subject to Public Act 436 (2012), commonly known as the “local financial stability and choice act.” Under this law, school districts, like local governments, can be identified as “fiscally stressed” and be required to submit additional data and reports to the state if they trigger one of 19 indicators. These may include missed payroll or bond payments, violating local government debt or budgeting rules, a very low credit rating and any other facts that, in the state treasurer’s estimation, threaten the fiscal stability of the district. While subject to this policy, school districts continued to enter fiscal deficit at an increasing rate. In 2015, the state thus decided to take a distinct approach to fiscal distress for school districts.

The laws enacted in early 2015 (PA 109-114) provide for an additional measure of fiscal distress specifically for Michigan public schools: budget assumptions. Any district with a general fund balance less than 5 percent in either of the two most recently completed school fiscal years is now required to submit the budgetary assumptions they used when adopting their annual budget. This information will ostensibly provide an indication of fiscal distress earlier than the 19 indicators enumerated in PA 436 (2012).

Expanding our conception of fiscal health

Expanding our conception of fiscal health

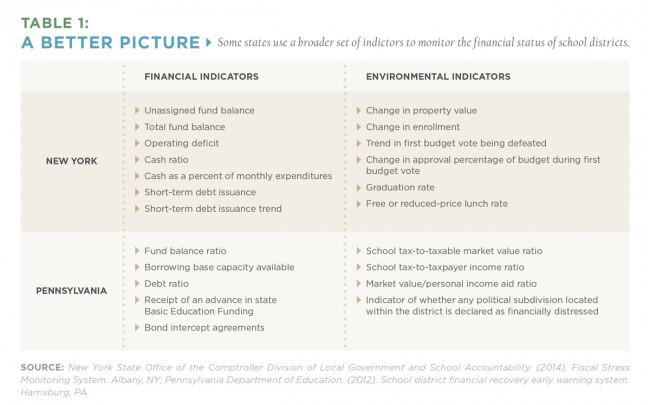

Michigan’s rudimentary list of solely static financial indicators of fiscal distress, and a single budgeting indicator—namely, general fund balance—as the trigger requiring districts to submit additional financial information “earlier” in the process contrasts sharply with other states that incorporate multiple financial indicators. These systems provide data on both school district financial and contextual conditions and provide each school district with a more robust, individualized measure of fiscal health.

For example, the state of New York’s Fiscal Stress Monitoring System evaluates every school district based on financial trends and ratio indicators as well as contextual and environmental indicators, such as property values and enrollment changes, as shown in Table 1. Colorado, Illinois and Pennsylvania, too, use numerous financial and/or environmental ratios.

While the collection and measurement of any data to provide insight into the conditions of school districts is important, the data must still be processed in order to present some overall assessment of a school district’s condition. Moreover, school districts must be able to make viable decisions and receive the necessary supports to improve their financial condition, while still meeting their obligation to provide public educational services to pupils. Thus, the processing of data and resultant actions must be part of a comprehensive system, tailored to the unique characteristics of school districts. The current Michigan system, however, is reflective of a one-size-fits-all system with all districts held to the same standards of fiscal distress regardless of the widely different financial and environmental contexts of Michigan’s more than 541 public school districts.

Implementing Michigan’s system

Implementing Michigan’s system

The effectiveness of the system will ultimately be revealed when the rubber meets the road—during implementation. Designing a viable, efficient and effective system via statute is difficult, making the work of those implementing the system even more paramount. While the Department of Treasury will have a significant role to play in determining whether this system successfully assists districts approaching or experiencing fiscal stress, numerous issues have already emerged out of the statutory language.

Issue 1: Five percent fund balance exemption

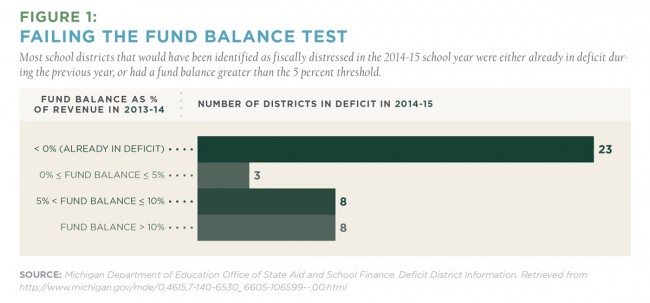

The arbitrary 5 percent fund balance threshold that serves as the starting point for Michigan’s early warning system may not provide the state with sufficient information about districts heading toward fiscal distress and may require districts not at risk of fiscal stress to spend time and resources on unnecessary reporting. In theory, a school district’s general fund balance would be indicative of fiscal health; in reality, this is rarely the case. More than four out of five of the districts that were new to deficit in 2014 had greater than 5 percent general fund balances in the previous school year and thus would not have been identified by the fund balance test. An even greater number of schools would have been identified as being potentially fiscally distressed, having less than a 5 percent fund balance, that ultimately were not fiscally distressed in the subsequent school year.

Moreover, holding every single school district, regardless of size and context, to the same fund balance threshold is illogical. Under the state’s “magic” 5 percent fund balance indicator, a district with an operating budget of $500,000 would be required to have as small as a $25,000 fund balance while a district with an operating budget of $50 million would be required to have a $2.5 million fund balance. If a school bus breaks down, requiring the purchase of a new one, the small district’s fund balance (plus more) will be spent entirely on this single purchase, whereas the large district will be able to make such a purchase while remaining fiscally solvent.

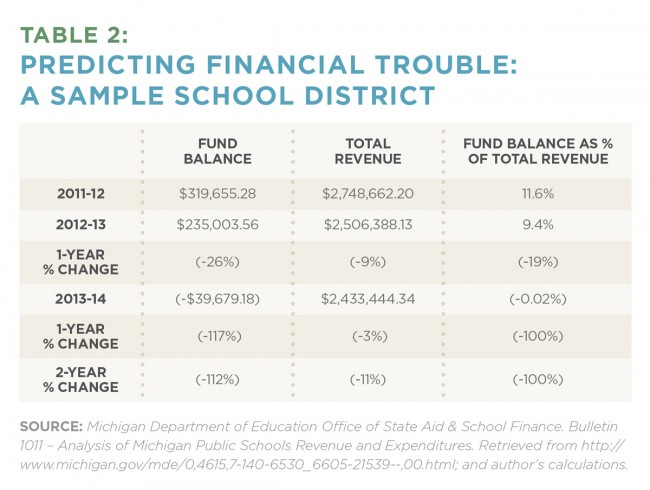

Conducting an in-depth analysis to better understand each district’s context will require significant time and resources. Take, for example, the level of review that would be required to more fully understand the potential for fiscal distress of a Michigan school district that did experience a deficit in 2014-15. The district examined in Table 2 is located in rural Michigan with one elementary and one middle/high school. Seventy-one percent of this district’s students are economically disadvantaged and 10 percent are non-white.

An examination of Michigan Department of Education data as well as the district’s publicly available financial audits show the district’s general fund balance to be above the 5 percent threshold in both 2011-12 and 2012-13. Thus, under Michigan law, the district would not be required to submit “early warning” budgetary assumptions for the 2014-15 school year. However, further analysis reveals that the district’s fund balance decreased by approximately 26 percent within a single fiscal year. This represents a significant drop when the total revenue for the district is just over $2.6 million. Someone familiar with this data, as opposed to static financial indicator data, would likely not be surprised by the district’s 2013-14 deficit.

Time and resources must be available to conduct such in-depth reviews of school district financial data and trends; a simple fund balance calculation is not enough. If troublesome trends such as those previously described are revealed, the likelihood of catching a financial issue prior to major disaster may increase, allowing the district to revisit their budget in a timely manner and/or to request assistance in the budgeting process.

Issue 2: Strategic avoidance of oversight

Issue 2: Strategic avoidance of oversight

Under Michigan’s new early warning system, school districts identified as potentially fiscally stressed have the option to contract with an intermediate school district (ISD), which is then charged with developing recommendations to resolve actual or potential financial stress. However, if a district does not contract with an ISD, the state treasurer could subject the district to additional reporting requirements if three criteria are satisfied:

(1) the district had a general fund balance of less than 5 percent for each of the two most recently completed school fiscal years,

(2) the district had a declining general fund balance in one or both of the two most recently completed school fiscal years and

(3) the district is not already required to submit a deficit elimination plan (DEP) or enhanced deficit elimination plan (EDEP).

The statutory language employs multiple conditional statements that could allow some districts to avoid both state and ISD support. For example, a school district that has not had a positive general fund balance of at least 5 percent for the two most recent fiscal years but whose general fund balance in the most recent school year increased could simply not partner with its ISD and also avoid state intervention.

Issue 3: Withholding funding from fiscally distressed districts

Finally, Michigan law allows for the withholding of funds from deficit districts in an amount “necessary to incentivize the district to eliminate the deficit” (MCL 388.1702 Sec. 102.1). The state also can require school districts to submit additional data and financial reports as fiscal stress increases. While access to and review of timely financial data is necessary in any effort to reduce fiscal stress, neither increased reporting nor withholding of funds will heal fiscal ailments in and of themselves. The logic behind such a system—withholding funds or requiring additional human resources from fiscally distressed districts—seems intuitively backward. Although providing districts with additional funding is not essential, we must ensure that they continue to receive funding necessary to carry out educational programming and services for children.

Simultaneously, these districts need assistance and expertise to remedy fiscal stress. While it remains to be seen whether the likely political decision to withhold district funds actually happens, it remains essential to ensure a system of supports and technical assistance is in place alongside reporting requirements.

Potential to help school districts

It is highly likely Michigan’s financial early warning system will unnecessarily burden some districts with additional reporting and allow some fiscally distressed districts to slip through the cracks. The system also allows for districts to circumvent intervention and provides for the illogical withholding of funds. However, state law does provide the Department of Treasury discretion to effectively utilize any available data to determine whether a school district is at risk for fiscal distress. Thus, there is room for the department to create a more robust system that factors in other indicators of fiscal distress. If the Department of Treasury has the financial and human resources to develop an effective, efficient, research-based fiscal monitoring system for school districts, while taking into account the unique institutional and administrative context of schools, there is potential that Michigan’s law can benefit school districts across the state.

Footnote

1 Given that Michigan’s public school academies and intermediate school districts, while subject to the early warning system, operate under funding allocation circumstances that differ from those of traditional public schools, this article focuses solely on Michigan’s traditional public school districts.

About the author

Rachel White was the author—alongside MSU Extension Specialist Eric Scorsone and MSU College of Law Professor Kristi Bowman—of two white papers that were utilized by state policymakers during the drafting of Michigan’s early warning law. She also co-led a seminar on Michigan’s early warning system in fall 2015 attended by the state treasurer, policymakers, intermediate and local school district superintendents, and research and advocacy groups.

On the web

MSU Extension white papers:

“Knowledgeable Navigation to Avoid the Iceberg: Considerations in Proactively Addressing School District Fiscal Stress in Michigan” and “Developing an Early Warning System for Michigan’s Schools”

msue.anr.msu.edu/resources/addressing_school_district_fiscal_stress_in_michigan

Legislation:

See Michigan Public Acts 109-114.

The content of this article reflects the views of the author and not necessarily those of Michigan State University or the MSU College of Education.