Student strives to improve language development for children with autism through audio analysis

By Nicole Geary

Nearly every week for the past two and a half years, Savana Bak has been greeting familiar groups of bright-eyed kids and helping them put on special T-shirts. Throughout the school day, she records all of their conversations using a small device tucked inside a chest pocket.

Language typically develops quickly while young children are attending school for the first time. But Bak, a special education doctoral student at Michigan State University, wants to understand how speech grows over time for students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD)—those who start school speaking very little.

She started capturing data on vocalizations from a group of kindergarten and first-grade children in a public school setting as part of her required practicum study. After analyzing a full year’s worth of audio, she discovered something shocking.

Out of nine students, only one made gains. In fact, six showed a decrease in the number of words spoken per minute and two remained relatively the same.

The LENA recording system is widely used to measure talk with children from birth to age 3. MSU scholar Savana Bak is among the first to use it with minimally verbal children with autism, particular those over the age of 5.

The vocalization rate for students (kindergarten and first grade) in her study who spoke the most is similar to the 75th percentile of a typically developing 2-year-old.

“It was really, really sad,” said Bak, noting the amount of time adults spent talking to the children did not seem to make a difference. “For children with ASD, they want to and start to share, but for them it may not be regularly understood or they communicate differently so it doesn’t get reciprocated as effectively.

“So, my hypothesis is, if reciprocation doesn’t happen, they talk less.”

Most language assessments for youth with ASD are based on pre- and post-testing, not multiple recordings, said Associate Professor Joshua Plavnick, Bak’s advisor. He believes she is one of the first researchers to use the Language Environment Analysis (LENA) recording system with minimally verbal children with ASD, particular those over the age of 5.

LENA is unlike regular recorders in that it counts and analyzes words and conversations. The system originated as a means to address the word gap for disadvantaged but typically developing kids from birth to age 3.

Another preliminary finding from her study shows that participants vocalized more frequently, about two words more per minute, while in special education classrooms than in general (inclusive) classrooms. Plavnick says the research, though in its early stages, illuminates the need for improved training and resources among educators who are striving to give students with ASD the best start they can.

“There is clearly a gap between what we know to be evidence-based practice and implementation,” he said.

Exploring the power of language

Unfortunately, the interventions that minimally verbal students with ASD need often occur outside of public schools, in private or university-based settings. One such environment is the Early Learning Institute (ELI) at MSU, where Bak has been continuing her research.

Growing up in Korea, she spent time with family members on the autism spectrum. She later worked as an elementary special education teacher and at a research institute in Seoul.

“I realized how much we all don’t know and how much we all need to know about individuals with autism,” Bak said. “And that is why I started this journey.”

She applied for the Special Education Ph.D. program at MSU after learning about an expanding research area: the Research in Autism, Intellectual and Neurodevelopmental Disabilities (RAIND) initiative. Increasingly, faculty members and students across campus are coming together to improve lives for individuals with autism and other disabilities in innovative ways (see page 4 for a recent example).

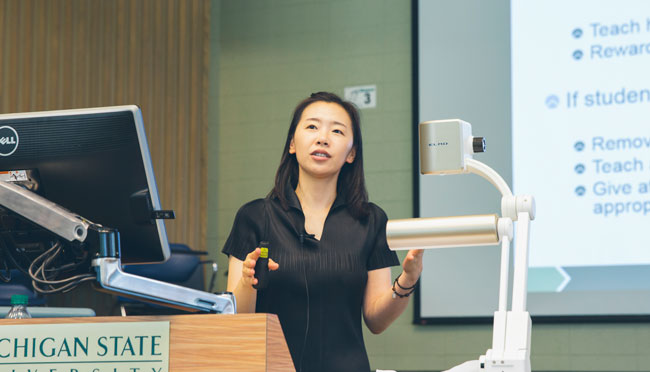

PICTURED:

Special education doctoral student Savana Bak has conducted research using language recorders worn by students with autism in public schools and at the Early Learning Institute (ELI), a unique preschool for children with autism operated by Michigan State University. Above, she helps ELI student Alex Semczuk.

From her very first class, Bak was immersed in collaborating with fellow students across disciplines. She felt encouraged to dive into research and welcome to venture into area schools.

“I would recommend the MSU experience to anyone,” said Bak. “It’s a very good blend of community service and also pure research.”

Bak first assisted with an experimental early reading intervention. She spent time in two elementary schools testing whether Headsprout, a popular online reading program, could teach children with ASD to read. With great success among a small group of students, College of Education faculty members including Plavnick, Troy Mariage and Carole Sue Englert have continued the research and shifted their focus to comprehension—exploring how to help students with ASD fully understand what they read.

The experience amplified Bak’s interest in using the power of language to improve communication and social acceptance. Educators are often focused on what students with autism do—their behavior—and not enough on what they say, she believes.

Creating an optimistic future

Bak still has much to analyze from the nine public school students she tracked over two years. The recordings add up to more than 165 hours for each child.

Meanwhile, she has been using the same Language Environment Analysis (LENA) recording devices and software to track development for 16 students enrolled at the ELI sites.

ELI provides a unique preschool experience for children with ASD, because they spend half of the day in intensive one-on-one behavior therapy and half with typically developing peers. The first site opened at the MSU Child Development Laboratory in fall 2015, followed by the second location in the Lansing School District this school year.

“It’s the dream site for a researching student because I can see the children every day. Watching them and interacting with them, I can get new ideas for studies,” said Bak, who has also been assigned to coordinate research projects at ELI by master’s students in the university’s new Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) program.

Previous research has shown that students with ASD need specific mediated instruction to learn language and engage in conversations. Bak will be watching closely to see if that is happening at ELI and if the results contradict with her first study.

She hopes to see gains, not drops, in students’ speaking and a smaller gap between the number of words spoken by adults and children. Ultimately, she hopes her work will inform positive changes for schools, as well as families.

Her next step following graduation is to land a job as a research faculty member, either in the U.S. or back in Korea.

“If I could find a way to help parents and teachers talk a little bit more effectively, to understand how language develops in children with autism, maybe it could increase the conversations in the household and the school, and maybe that would facilitate the social communication that so many individuals with autism are having trouble with,” she said. “I’m very optimistic. I mean if you’re not optimistic, why are you doing this?”

Savana Bak

Hometown: Seoul, Korea

Level: Third year, Ph.D. student

Program: Special Education

Faculty advisor: Joshua Plavnick, Associate Professor of Special Education and Director, Early Learning Institute

Financial support: Graduate assistantship program support, the Anderson-Schwille Fellowship in International Education and the Practicum Research Development Fund