Research examines how students discuss issues like immigration, internet privacy

Professor Margaret Crocco, Professor Avner Segall, Associate Professor Anne-Lise Halvorsen & Associate Professor Rebecca Jacobsen

Department of Teacher Education

Educators deem developing students’ skills, knowledge and positive regard for civil political discourse through classroom discussions and deliberation essential to their civic efficacy and political participation. Yet, while there are many examples of what not to do or say in the context of talking politics, examples of civil political discourse—including among politicians, the media and adults on social media—are in short supply.

Margaret Crocco

Avner Segall

At the same time, we are living in a period of unprecedented access to information. There are more sources for news than ever before in history. As of August 2017, two-thirds of Americans reported that they get at least some of their news from social media (Shearer & Gottfried, 2017), “fake news” sites are on the rise and false news spreads faster than true news (Vosoughi, Roy, & Aral, 2018). In this environment, individuals need tools to determine sources’ credibility and trustworthiness, a tall order when they are faced with a barrage of so much information.

Anne-Lise Halvorsen

Rebecca Jacobsen

These challenges—information overload and rampant incivility—are particularly acute for today’s youth, who are at a pivotal stage in their development, and who are increasingly being expected to deal smartly with the credibility of sources in school (as outlined in the Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science and Technical Subjects). Additionally, they are growing up at a time in which their president has declared the press “the enemy of the people” (Phillips, 2018). How do youth consider the trustworthiness of the vast amounts of information they encounter? How do they draw on evidence in discussions of public issues with their peers? How do fake news and “confirmation bias” circulate and advance particular ideological and ethical positions in discussions of public issues? How do students deal with this barrage of information, analyze and synthesize it and then share their opinions with their classmates in reasoned, civil ways?

DEMOGRAPHICS, EVALUATION & EVIDENCE

In 2015-16, we sought to answer these questions with the support of a grant from the Spencer Foundation. We conducted research in four Michigan high school classrooms with distinct demographic profiles. Specifically, we studied students’ evaluation and use of evidence in a range of ways. We asked students (N=90) to rank-order evidence from least-to-most trustworthy in “the abstract”—that is, devoid of any historical or political context—as well as in the context of a “settled” historical issue. Then, we observed classroom discussions of two public issues: one on immigration policy and the other on internet privacy in which students were instructed to draw on evidence to support their claims.

Our findings emphasize the need for teachers to … foster dispositions toward more intent listening across differences if we hope to engender more thoughtful and productive civic deliberations about important policy issues.

What we found is that evidence use is not straightforward; instead, our research revealed interesting intersections between students’ demographic characteristics (gender, race, social class and immigration status) and their evaluation and use of evidence in classroom deliberations, and that what may appear haphazard or random is actually rational and thoughtful. We also learned that although these students’ teachers are committed to engaging them in deliberations of public issues, they do not feel well prepared to do this, especially given today’s challenging political context.

“Our findings suggest great urgency for educators and researchers to better understand the complex web of youth, media, public issues and civil discourse.”

PHASE 1: HOW DO STUDENTS EVALUATE EVIDENCE?

As youth engage with social media as a primary (if not the only) source of news and information, it is important to understand how they come to form judgments about what constitutes “good” evidence. While conventional wisdom tends to frame evidence as numbers or facts, there are, in fact, many different types of evidence, including personal experience, statistical data, expert judgment and examples.

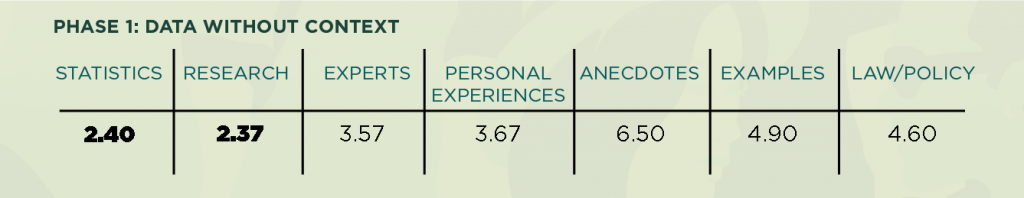

To get inside students’ thinking, in our study, we asked them to engage in a simple card-sorting activity, ranking them in order from least to most trustworthy. Each card had one of seven kinds of evidence:

- statistical data,

- research,

- expert judgment,

- personal experience,

- anecdotal/second-hand experience,

- example (such as a photo) and

- law/policy.

As students sorted their cards, we asked them to “think aloud” to share their process for determining their ranking. We then analyzed the resulting rankings and the comments students made as they completed the task.

Students thoughtfully described the multiple ways they evaluated evidence. Overall, we found a great deal of variation in trust of different kinds of evidence among students. For example, while some expressed blind faith in numbers, calling it the “most objective information,” others pointed to the ways flaws in sampling can create misleading data, and still others recognized that “statistical data can be wrong” or wrongly interpreted. Additionally, students’ ideas were not fixed; as the context of the issue changed, so, too, did the students’ reasoning. For example, despite many students’ ability to articulate the multiple ways personal experiences can be a problematic form of evidence in the abstract, it was the personal narratives that were considered most persuasive by many students when they evaluated evidence in the context of Brown v. Board of Education. Students repeatedly noted that emotional connections to the evidence were key in the context of Brown or, as one student stated, “the personal experience really tugs at my heartstrings.”

The insights of these students help us comprehend the complexity teachers face when teaching about and with evidence. It requires not only understanding the issue and related evidence, but also one’s students in order to help them realize the ways their biases, experiences and preferences shape how they view evidence (Jacobsen, Halvorsen, Fraser, Schmitt, Crocco, & Segall, 2018).

PHASE 2: THE ROLE OF STUDENTS’ DEMOGRAPHICS IN DISCUSSIONS

The next phase of our research focused on studying students’ interactions and responses in the context of two public policy discussions. We found that factors of student identity—gender, race, ethnicity, social class—impacted students’ positions and participation pattern in the discussions. For example, male students, particularly in heterogeneous classrooms, tended to dominate both the substance and dynamics of the deliberation, with female students mostly responding to—and at times challenging—the views raised by male students but rarely setting the agenda of the discussion. Gender also played an apparent role in stances toward immigration policy. Male students in the classrooms we observed tended to suggest that immigrants do not contribute to the economy, drain the welfare system and pose a danger to U.S. national security and Americans’ personal safety, hence calling for a more restrictive immigration policy. Most female students, on the other hand, blamed unreasonable U.S. policies and international economic and political systems for the plight of immigrants. They spoke more consistently about the human aspects related to immigration and focused on the need to care for and support immigrants collectively and individually. We noticed a similar overall pattern when it came to white students on the one hand and non-white and immigrant students on the other, with the former raising economic and security issues that suggested restricting immigration while students of color and students with a more recent immigration history suggesting a more social justice-oriented approach.

We also found that students from higher socioeconomic classrooms tended to use more academic language to discuss immigration issues but, in doing so, distanced themselves from the human aspects associated with immigration. Students from less affluent classrooms displayed less academic language in their discussions but highlighted the human aspects of immigration and its consequences, showing empathy to immigrants as human beings. They tended to be more critical of federal policy that, in their view, ignored the human toll resulting from it. Despite these differences across classrooms, most students, regardless of gender, ethnicity, race, socioeconomics or immigration status, appeared to create a division in their rhetoric between “we” (those of us already in the U.S.) and “them” (those attempting to enter the country), creating a common identity for Americans, on the one hand, and immigrants who desire to become Americans but who are not yet so, on the other.

Our findings emphasize the need for teachers to consider issues of identity when planning for and conducting deliberations as well as the need to foster dispositions toward more intent listening across differences if we hope to engender more thoughtful and productive civic deliberations about important policy issues.

STUDENTS’ INCORPORATION OF “FAKE NEWS” IN DISCUSSIONS

The discussion of immigration policy, conducted during the 2016 presidential race, revealed some fascinating findings about the kinds of evidence students felt were compelling. As the discussion unfolded, students were divided over whether policy should focus on lessening illegal immigration, opening borders up or allowing only high-skill or high-wealth immigrants into the country. When we analyzed the video recordings of the deliberation and written transcripts, we saw that students were engaged in what’s been called “motivated reasoning” (Kahne & Bowyer, 2017). They made highly selective use of the evidence, ignoring items that might challenge their opinions.

They also introduced outside information from highly partisan sources of questionable credibility to support their arguments. For example, several students circulated “fake news” that immigrants were a threat to the public order and personal safety. In fact, the contrary is true: Immigrants commit crimes at a lesser rate than citizens in the U.S., a fact that was included in their evidence packet but was ignored in favor of the evidence that supported their pre-existing beliefs. Another student introduced a barrage of statistical information from a highly partisan website that silenced others in the class who seemed unable to challenge or question the many statistics being cited as unimpeachable truth.

We concluded from this research that students, like adults, may be motivated to avoid evidence when it does not confirm their biases, thus defending themselves against facts that trouble their assumptions and understanding of themselves, others and the world. Educators will need to be alert to such rhetorical maneuvers in their classrooms if they are to engage in discussion and deliberation of sensitive issues in civic and history classrooms.

STRIVING FOR DISCOURSE IN AN UNCIVIL WORLD

In our study, we selected teachers known for their commitment to engaging students in discussions of public issues. However, even these experienced teachers struggled in various ways in preparing for and facilitating discussions. Based on our research, we developed a set of guidelines for establishing a productive discussion (Crocco, Halvorsen, Segall, & Jacobsen, 2018):

- Establish a classroom community. A school climate that promotes tolerance, trust, open-mindedness and critical inquiry of one’s own ideas as well as those of others is critical to help young people learn to deliberate in a civil fashion.

- Ask students to help define the ground rules. Students should be involved in establishing rules to follow in classroom discussions. By coming up with rules themselves, they will be more likely to have ownership of them and an investment in ensuring their success.

- Select topics carefully with student interest in mind. Topics should also elicit different perspectives to ensure a lively and substantive discussion in which students consider opposing viewpoints.

- Ease slowly into classroom discussions. Students should have an opportunity to talk in pairs or small groups before engaging in whole class discussions; that way, they have the opportunity to test out their ideas and thoughts in a less formal, less intimidating setting.

- Vary the format. Teachers should try different formats to engage typically quieter students, to enhance students’ listening skills and to provide students different kinds of discussion opportunities that are similar to what they might experience in the world beyond school.

- Go beyond pro and con. Discussions are often most interesting in the space that is neither “pro” nor “con,” but one that seeks compromise or an alternative resolution than one side or the other.

- Be an active facilitator. Teachers’ instructional moves are often critical to the success of a discussion. These instructional moves entail reminding students of ground rules, physically setting up the classroom for a conducive discussion, injecting oneself in the discussion to clarify points, reminding students to draw on evidence, inviting quieter students to participate (and likewise, encouraging more vocal students to take a step back), challenging claims and summarizing the discussion.

In conclusion, engaging students in civil political discourse requires time, effort, resources and skills. We believe and our research shows it’s worth the investment. Young people are not interested in participating in a political system they find ineffective. It’s time for schools to step up and help youth see the power and promise of civil discourse, despite its difficulties.

REFERENCES

Crocco, M., Segall, A., Halvorsen, A., & Jacobsen (2018). Deliberating public policy issues with adolescents. Democracy and Education, 26(1), Article 3.

Crocco, M., Halvorsen, A., Segall, A., & Jacobsen, R. (2018). Less arguing, more listening: Improving civility in classrooms. Kappan, 99(5), 67-71.

Crocco, M., Halvorsen, A., Jacobsen, R., & Segall, A. (2017). Teaching with evidence. Kappan, 98(7), 67-71.

Jacobsen, R., Halvorsen, A., Frasier, A. S., Schmitt, A., Crocco, M. S., & Segall, A. (2018). Thinking deeply, thinking emotionally: How high school students make sense of evidence. Theory and Research in Social Education, 46 (2), 232-276, doi: 10.1080/00933104.2018.1425170

Kahne, J., & Bowyer, B. (2017). Educating for democracy in a partisan age: Confronting the challenges of motivated reasoning and misinformation. American Educational Research Journal, 54(1), 3–34, doi: 10.3102/0002831216679817

Phillips, A. (2018). Sarah Sanders presents the official White House policy: The media is the enemy of the people. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2018/08/02/sarah-sanders-presents-the-official-white-house-policy-the-media-is-the-enemy-of-the-people/?utm_term=.f2e32f00fcea

Shearer, E., & Gottfried, J. (2017, September 7). News use across social media platforms 2017. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.journalism.org/2017/09/07/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-2017/

Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359 (6380), 1146-1151 doi: 10.1126/science.aap9559