Over the course of childhood and adolescence, how do we grow and learn motor skills, such as jumping, throwing and running? What changes in our body, brain and environment influence our physical maturation and skills?

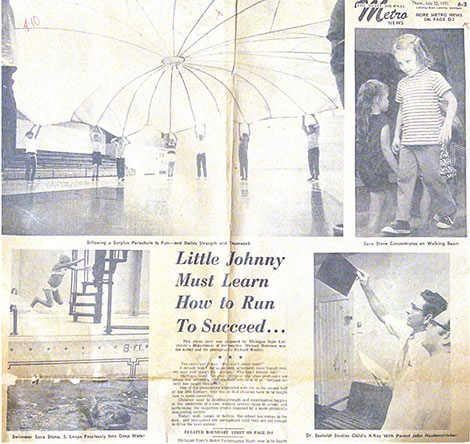

These questions, among others, were examined in a decades-long study at Michigan State University that began in 1967. The MSU Motor Performance Study (MPS) was a unique blend of innovation, community collaboration, focus on service and a drive to find answers—many of which are now featured in a special issue of Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science.

MPS was conceived and implemented by Professor Emeritus Vern Seefeldt as part of his responsibility to develop a research-based motor development program within the then-called Department of Health and Physical Education.

“I was always intrigued by motoric functions of the human body,” he said. “I was interested in how children learned motor skills and the tremendous possibilities that motor competence provided for individuals in terms of social development, academic achievement, sport performance and healthy, lifelong leisure activities.”

The study, at first planned to span 10 years, followed children and youth to examine physical growth, biological maturity and gross motor skill acquisition. It eventually expanded to last for more than 30 years, gathering the data of more than 1,200 participants from Michigan.

In the special journal issue, MSU scholars—including Professor Emeriti Seefeldt, John Haubenstricker and Crystal Branta, current Department of Kinesiology Professor Karin A. Pfeiffer, and many doctoral students and alumni—examined the expansive data.

Key findings include the influence of environment and activity in childhood and how it affected factors later in life.

One study found those who exhibited lower levels of fitness early in childhood were likely to exhibit lower levels of fitness later in adolescence. Yet, overall, fitness levels of participants tended to be favorable compared to the general population.

Another study found similar results regarding sports: Children who did not participate in recreational sports were less likely to be in multiple sports in high school. In addition, it increased the likelihood they would not participate in sport in college.

Over the course of its 36-year history, MPS included:

- Instruction: Participants learned throwing, catching, kicking, punting, striking, jumping, running, hopping, galloping and skipping, and a variety of sport-specific skills. Participants ranged from 2 to 18 years of age.

- Education: MSU kinesiology undergraduate students and local teachers were central to the success of MPS, providing much of the instruction for participants.

- Research: Scholars identified and tracked physical changes over time, how skills were learned and the influence of their environment in learning those skills.

Community effort

MPS began by doing something that had never been done before.

“At that time, sport participation was conducted by Little League Baseball, Itty Bitty Basketball and other similar programs. Children would try out and only the most skilled were invited to participate,” Seefeldt recalled. He came to MSU as an assistant professor in 1966, at the request of Gale Mikles, chairperson of the the department. “I felt that was wrong. Everyone should have the opportunity to become proficient in sports, especially those related to fundamental skills.”

When it was announced to the local community that MSU was seeking enrollees in a new physical recreation program, open to anyone aged 2.5-8 years of age, there was an overwhelming response. The Lansing State Journal ran a story about the program in Nov. 1967.

A history book on the MSU Kinesiology program (“100 Years of Kinesiology: History, Research and Reflections,” MSU Printing Services, 1999) explained what happened next: “Although no telephone numbers were provided in the article, by 8:00 a.m. the next day, the MSU switchboard was inundated with requests for information … By afternoon on Nov. 13, 1967, the quota of 110 enrollees had been filled. In addition, another 171 potential enrollees requested application forms. A waiting list for entry into the program existed well into the 1990s.”

The clinic, which ran from January 1968 through summer 1994, began with classes taught by MSU undergraduates, under the supervision of experienced physical education teachers. Each class, which expanded and shifted as the children aged and younger cohorts were brought on, provided developmentally appropriate instruction and activities. Young children began by learning fundamental skills like running, balancing and kicking, as well as being offered swim and ice skating lessons. The classes continued to progress to build fundamental sport and dancing skills, all the way to offensive and defensive skills and strategies in particular sports.

“The primary feature of the study was to determine the relationship between biological maturity, physical growth and motor function, and the interrelationship between those,” Seefeldt said. “We found that learning fundamental movement skills was an essential component of healthy development.”

As time passed, MSU faculty and instructors learned some participants benefitted from more one-on-one or specialized instruction, and off-shoots of the main clinic were created. One example—the Sports Skills Program, assisting children and adults with disabilities to learn and improve sport skills—is still in existence today.

“The teaching clinic was something that really set MPS apart,” said Karin Pfeiffer, who now serves as the “custodian” of the data. “Many other studies, at the time, didn’t have the hands-on learning and development component.”

Other featured authors in the issue—Professor Emeritus John Haubenstricker and Associate Professor Emerita Crystal Branta—had, at one time, played a key role in the history of MPS. Haubenstricker, co-author of “100 Years of Kinesiology,” served as MPS coordinator from 1978-99. Branta was the lead “custodian of the data” until passing on the legacy to Pfeiffer.

The story of the data

The momentum of the special issue started when two Kinesiology alumni, Eric Martin (Ph.D. ’16) and Larissa True (Ph.D. ’14), wanted to use the data for a statistics class. It continued with presentations at a North American Society for the Psychology of Sport and Physical Activity’s annual conference, where participants suggested creating a special issue.

Lisa Barnett, associate professor at Australia’s Deakin University, was one of many voices making the suggestion—she later became a guest editor for the issue. Beverly Ulrich, Ph.D. ’84 (Health and Physical Education), joined as another guest editor. She is dean and professor emerita at University of Michigan’s School of Kinesiology. Their participation—as well as from Associate Professor Nicholas D. Myers, who serves as Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science‘s editor-in-chief—guided the special issue in numerous ways.

Journal contributors examined the study’s data, which includes semi-annual assessments by MSU scholars on 13 measures of physical growth and seven measures of motor performance of the participants. The measurements included weight, height, shoulder and hip width, as well as performance on a 30-yard dash, beam walk and standing long jump.

According to one study in the special issue, boys outperformed girls on all fitness measures at all points, except at the age of 6 and with the exception of the flexibility measure.

The data also suggested, according to another study, that those who excelled in endurance, speed and agility were more likely to participate in sports in high school. Boys and girls at all ages who participated in the study performed better than a national sample on tests of physical fitness, although improved competence in motor skills (rather than fitness) was the objective sought in the MPS.

“The study was important because of the lens it took,” Pfeiffer explained. “It provided a contribution to the understanding of how skills developed over time. Other studies at the time were looking at things like fitness and performance; what they didn’t do was follow fundamental motor skill development.”

It was also important because of the lifelong effect it had on the participants, argued Pfeiffer, director of the Department of Kinesiology’s master’s and doctoral programs.

In the early 2000s, over 250 participants responded to a follow-up survey more than a decade after the conclusion of the clinic, asking about their physical fitness and activities. Findings from the data are included throughout the special issue.

“When you look at how physically active participants were when we followed up, they were still pretty active—and it’s because they learned to move,” she explained. “The study showed how important it was and is to learn these building blocks.

“That is something physical education in schools can do—help children learn general movement skills that can transfer and help throughout their lifetime. Physical education gives a wide base from which you can operate, and we found it does relate to how physically active people will be later in life. What will we be doing to future generations if physical education is removed from schools?”

The authors noted many of the findings merited further review, and also noted that the data were collected from so long ago.

Yet, the authors—including Pfeiffer and Seefeldt—argue that is exactly why looking at longitudinal data, such as that provided by MPS, is important. Scholars can look to the past to understand the current state—and to plan for the future.

Relates news & resources

Read the special issue of Measurement of Physical Education and Exercise Science.

Vern Seefeldt was the inaugural director of the Institute for the Study of Youth Sports, created in 1978. Like the MPS study, the Institute found “all children could have great experiences in sport,” Seefeldt said. In 2018, the Institute celebrated 40 years of research to support and amplify sport opportunities for youth. Watch a conversation between Seefeldt and Professor and current Director Dan Gould.

Karin Pfeiffer was elected to the National Academy of Kinesiology in 2020. She was also one of three Spartans (including Department of Kinesiology Professor and Chair Alan Smith and alumna Meredith Whitley) to be named to the 2020-21 President’s Council on Sports, Fitness & Nutrition Science Board.