The Education Policy Innovation Collaborative, or EPIC, at Michigan State University was created to work with education policymakers and stakeholders to conduct research that directly informs important policies in education. So when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, EPIC researchers immediately began studying its impact. How would decisions made by public school leaders affect students, educators and the broader community?

As the strategic research partner for the Michigan Department of Education, EPIC has worked hand-in-hand with officials to collect and analyze frontline data from nearly every Michigan school district at key stages in the journey—a partnership few, if any, other states can match.

The work has gotten the attention of leaders. EPIC Faculty Director Katharine Strunk has presented findings to statewide professional associations, the state Board of Education and the Senate Education Committee. Her research with Professor Scott Imberman and colleagues on whether schools spread COVID-19 was cited by the U.S. Senate Joint Economic Committee and used by Gov. Gretchen Whitmer as evidence in her recommendation for all Michigan schools to return to in-person learning by March 1, 2021.

From the start, the MSU Office of K-12 Outreach has also created important resources for educators during the pandemic. This office, also based in the College of Education, provides customized support for schools and districts in Michigan.

There’s still much to consider, such as just how much students’ learning has been shaped by a year of remote or fractured schooling.

Explore the timeline of statewide actions and research findings below.

MARCH 2020

The novel coronavirus arrives in the U.S.

Michigan suspends face-to-face instruction in schools beginning on March 16, 2020.

APRIL 2020

RESPONSE BY STATES

The Education Policy Innovation Collaborative (EPIC) at MSU releases a comprehensive report on how every state is—or is not—providing guidance to schools on how they respond to the new challenges of COVID-19. The study, a partnership with MSU’s Institute for Public Policy and Social Research (IPPSR), finds state actions vary greatly across states. For instance, different states put forth disparate guidance and recommendations about whether they require distance learning and if they give direction on special education. The researchers recommend extending the school year, revising testing, investing in teacher professional development and funding alternative forms of distance learning.

EPIC and IPPSR researchers have continued to update this searchable database, providing a valuable perspective on how state policies shift over time and compare to one another.

MAY 2020

REOPENING GUIDANCE

The MSU Office of K-12 Outreach distributes a reopening guide for schools to help leaders plan for and mitigate the risks of COVID-19 during the forthcoming school year. The guide includes an overview of recommendations and considerations regarding classroom- and building-level changes, shifts in schedules and placing students in cohorts.

JULY 2020

SPRING LEARNING

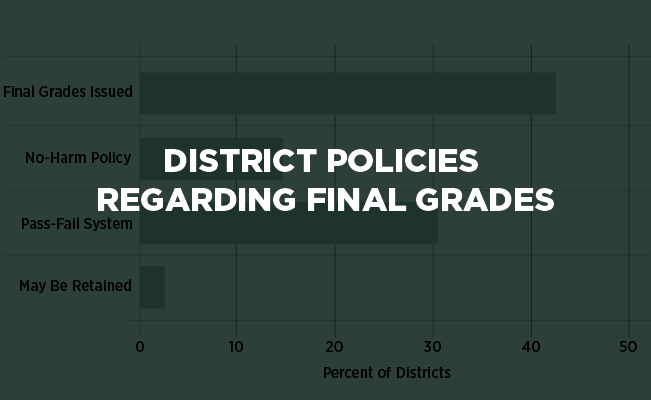

EPIC shares a report with state leaders about the ways in which Michigan school districts provided remote learning during the spring and included considerations for how they might learn from their experiences. This analysis, based on Continuity of Learning plans required of each district, found that school location, family income and broadband internet access were critical factors in how well students adjusted to the shift from classroom to remote learning. They found, for example, that most districts were flexible with final grading policies and specified resources for mental health and nutrition. Only a quarter of districts, however, planned to offer their teachers professional development on distance learning.

AUGUST 2020

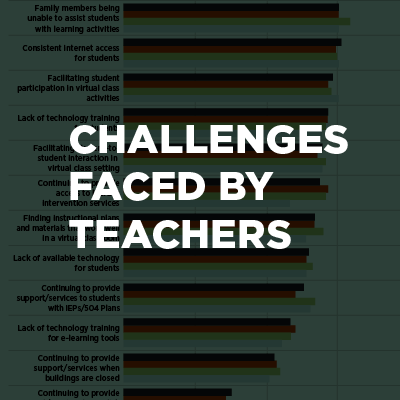

ASKING EDUCATORS

A statewide survey of nearly 9,000 Michigan educators conducted by EPIC shows their top pandemic-related concerns were for students: lost instructional time, trauma and limited access to meals and counseling. The researchers argue that policymakers, not only in Michigan, should “use this evidence to better understand—from educators’ own perspectives—where the gaps may be greatest and what needs to be done to ameliorate them.”

*An update to this survey was reported in spring 2021.

FALL PLANNING

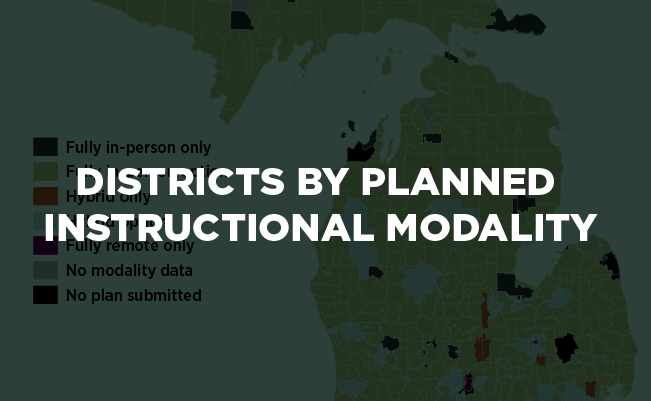

EPIC releases a report on how Michigan school districts expect to offer instruction in the fall. Of the 823 districts that provided Return-to-Learn plans, 86% say they will offer some or all instruction in person at the beginning of the school year. Fifty-nine percent say they will offer students at least the option to return to school five days a week, and 27% will provide the ability to return to school at least two to three days a week.

NOVEMBER 2020 AND CONTINUING

REMOTE REALITIES

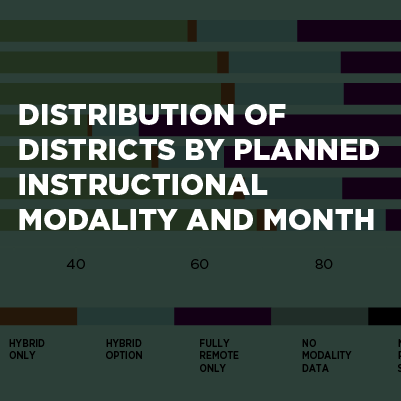

With the new school year underway, EPIC and its state partners begin regular reports on how students are learning during the pandemic. The November report shows that even though the majority of Michigan school districts planned to offer full-time in-person instruction, far fewer families actually choose this form of instruction. Additionally, districts with high proportions of Black and poor students were much less likely to provide students the option to learn in person five days a week.

In December, Michigan school districts report a dramatic shift toward remote instruction. Of all school districts in Michigan, 32% switched from planning to offer some in-person instruction to going fully remote only, representing a 200% increase in the share of districts providing fully remote instruction. In February, however, there was a 50% decrease in the proportion of districts only offering remote instruction, as many districts shifted to hybrid or in-person learning.

*The monthly collection of data and reporting on district Extended COVID-19 Learning Plans continues. EPIC also pairs each report with a spotlight analyzing the impact on special student populations.

JANUARY 2021

MSU scholars make news when they share a bold assertion from their work: Schools that offer in-person instruction do not contribute to the spread of COVID-19 in nearby communities if the number of people with the disease is relatively low. But if case rates are relatively high—in Michigan, in the top quartile of districts in the state—COVID-19 spread may increase. To reach this conclusion, they used data from September through December 2020 in Michigan and Washington states—both of which allowed districts to decide whether or not to offer in-person schooling at that time—to analyze how these different instructional decisions affect COVID-19 case rates.

READ MORE

Find all COVID-19 related reports, working papers and policy briefs from EPIC. Want these updates as they happen? Join the EPIC mailing list!