The path to becoming a professor in the U.S. is highly competitive. The numbers of foreign-born faculty and faculty of color are growing, making institutions more diverse. But are these scholars experiencing equal opportunities along the way? Two Michigan State University researchers say no—and they are teaming up to explore how higher education could do better.

“We say we need to educate a diverse group of students, but we don’t have diverse faculty,” said Dongbin Kim.

Most of the discussion around increasing diversity at universities focuses on differences in who people are—their gender, race or nationality.

Kim and Brendan Cantwell want to know more about where faculty members get started. How selective was the institution from which they received their bachelor’s degree? How does that predict where they will earn a Ph.D. and eventually get hired? And how do these trends differ between groups?

They are embarking on research that will analyze the academic paths of thousands of U.S. faculty members in the STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) fields, using data from the National Science Foundation (NSF) Survey of Doctorate Recipients and Survey of Earned Doctorates, plus individual curriculum vitae.

Brendan Cantwell and Dongbin Kim, both faculty members in Higher, Adult and Lifelong Education (HALE) at Michigan State University, are collaborating on research that will explore how the selectivity of baccalaureate and graduate-level institutions affects career prospects for U.S. faculty in the STEM fields.

Cantwell and Kim, both part of the Higher, Adult and Lifelong Education (HALE) faculty at Michigan State, say it’s not enough to increase the total number of doctorates among women and individuals of color in STEM—an oft-cited goal in the U.S.—if they are not distributed across a range of institutions, including the most selective.

“Evidence suggests where you do your Ph.D. matters,” said Cantwell. “We want to know the odds of becoming a faculty member at a prestigious university based on who you are but also where you start your academic career.

“This can serve as a guide to help policymakers identify the most important points of intervention.”

The pair’s preliminary research focused on individuals who earned their doctorates in two fields, education and engineering. They found that the more selective the undergraduate institutions individuals graduated from, the more likely they received doctoral degrees from highly selective doctoral programs.

Further, they found the distribution of doctoral graduates by race/ethnicity across the various types of institutions has changed since the 1970s. Back then, roughly a quarter of engineering graduates from each race (white, black, Hispanic and Asian) went to the top-25 institutions for their Ph.D. By the 2000s, the percentage in the upper tier jumped for whites, to 33 percent, and Asians, to 37 percent, compared to 22 percent of blacks and 27 percent of Hispanics.

Further, they found the distribution of doctoral graduates by race/ethnicity across the various types of institutions has changed since the 1970s. Back then, roughly a quarter of engineering graduates from each race (white, black, Hispanic and Asian) went to the top-25 institutions for their Ph.D. By the 2000s, the percentage in the upper tier jumped for whites, to 33 percent, and Asians, to 37 percent, compared to 22 percent of blacks and 27 percent of Hispanics.

Kim and Cantwell have started by studying doctorates who are American citizens but they also plan to explore the academic paths of foreign-born faculty members, a rapidly growing portion of STEM faculty in the United States.

Both have already uncovered challenges faced by international faculty in their own work.

Foreign-born scholars earn over half of all STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) advanced degrees in the United States. How does their experience differ after graduation?

The foreign faculty experience

Kim was one of the first to study foreign-born faculty in the United States when she started five years ago. She has a unique perspective as a native of Korea who earned her Ph.D. at UCLA.

While there have been significant increases in the representation of foreign-born faculty in U.S. higher education institutions, especially in STEM fields, little research has examined their professional career experiences.

“International faculty members are a highly sought-after source of human capital and we need to do more to understand what shapes their professional experiences,” she said. For example, her research has found foreign-born faculty are less satisfied but more productive in publishing than peers, and are less likely to pursue administration.

With her research, Kim suggests the need to provide professional development and mentoring services that are tailored toward the unique needs and challenges that foreign-born faculty encounter on campus.

The problem with post-docs

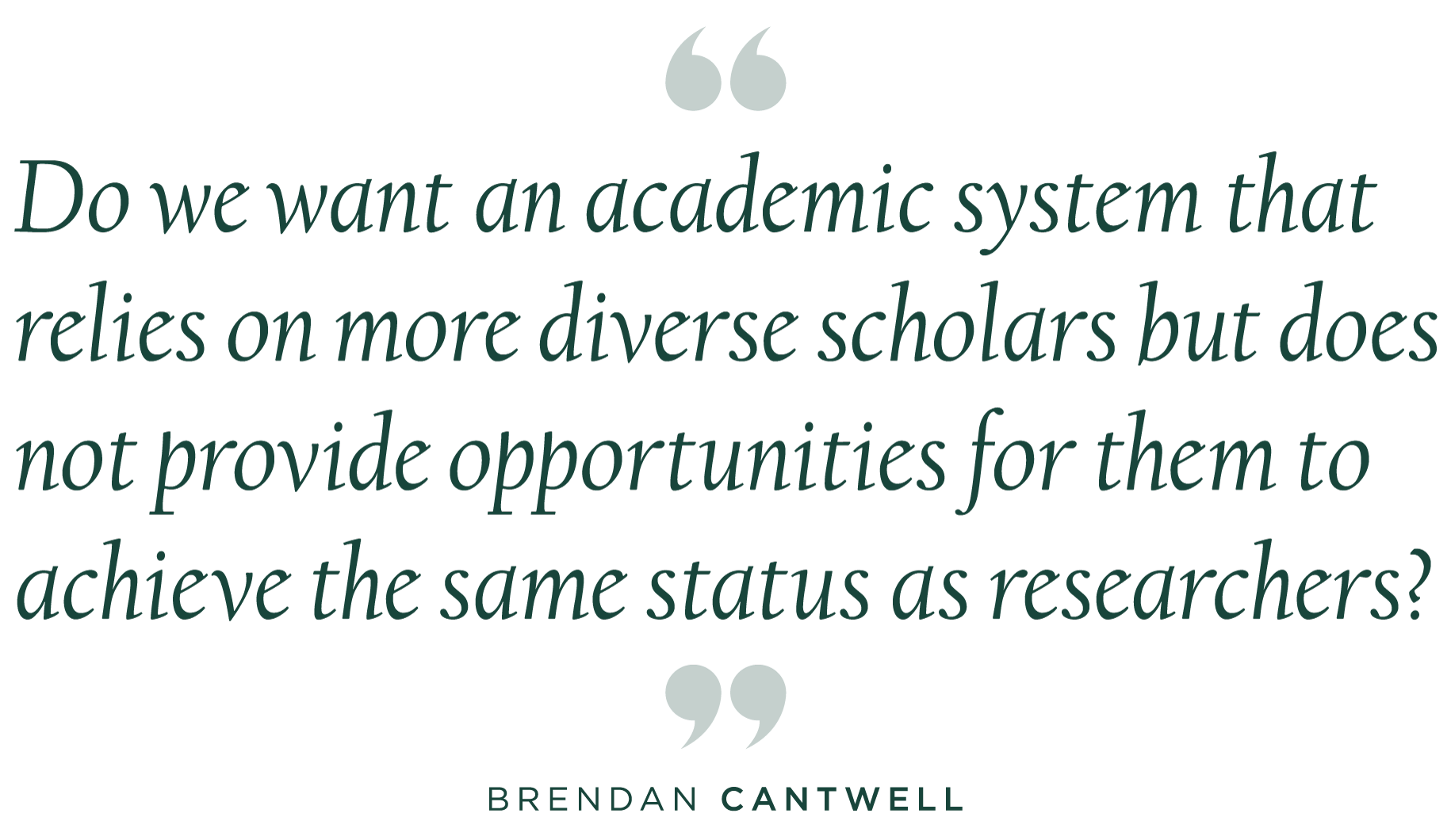

Similarly, Cantwell’s research on post-docs illuminates differences between domestic and international scholars. His recent study found that reasons for working as a post-doc after graduation—rather than being hired as a tenure-track faculty member—differ by race and foreign-born status.

In particular, foreign-born Asians and those who identify as black are much more likely than their white U.S. counterparts to accept a post-doc job because no other options are available. The positions were originally intended to provide additional professional training. The number of researchers taking post-docs, and for much longer periods of time, has been on the rise in the STEM fields.

“It suggests there is some type of bias or a challenge in the labor market,” said Cantwell. “We need to think about what type of academic system we want. Do we want one that relies on more diverse scholars but does not provide opportunities for them to achieve the same status as researchers?”